The Beesley Lecture

A speech by Andrew Haines, Transition Team Lead

2 November 2022

Hello and good evening. Thank you for coming this evening to a subject that is perhaps on the margins of the Beesley agenda.

Let me state right at the outset that Britain’s railways face huge challenges and opportunities. But as someone who has been involved in the structure of the sector for some 30 years, and as someone with some insight into regulation from my time as a regulator, I do not believe that the nature of regulation in the railway is either a fundamental factor in its current challenges nor indeed a potential game-changer in its future.

So, whilst I’m unaware of the organisers' refund policy, let me apologise now to anyone expecting profound thinking on the role of regulation in a restructured rail sector. There are others, not least Chris and indeed distinguished members of the audience, who are better placed to offer a perspective on that.

Secondly, let me, at least half-heartedly, apologise for something of a history lesson, or at least a reprise of the last 30 years of the railway’s journey. Where the sector finds itself today and the core thinking behind the Williams rail review can only, I believe, be understood if we spend some time looking at how we got to where we are.

And one final opening remark from me – the railways are old.

In 2025 we will celebrate the 200th anniversary of the first regular passenger rail service on the Darlington to Stockton Railway.

And as a result, we often make the mistake of not stopping to think about what the railways are for, what they are good at, and what they are less well designed to achieve.

As possibly one of the oldest of the public utilities, it is easy to take this for granted. And indeed, I suspect I’m going to succumb to that particular strain of sinfulness myself tonight. Not because I believe the railway is good at everything or that it is reasonable to demand investment for an ever-growing list of ideas and initiatives that will increase its capacity and footprint. Nor indeed because I am indifferent to the fundamental shifts in demand that a decarbonised economy, the return of congestion, the introduction of HS2 to name just three, might bring. But simply because that’s not the question that the Rail review seeks to address.

It is a sobering reality check that Keith Williams was appointed just over four years ago to undertake a fundamental review of how Britain’s railway system was functioning. That review was precipitated not by some grand vision for the future but by an urgent political imperative.

An imperative driven by some fundamental cracks in the system:

- the high profile mess of the May 2018 timetable introduction

- the collapse of the East Coast Mainline franchise for the third time

- a significant decline in the number of bidders in the franchising market, and a recognition in Whitehall and Westminster that a system where the only one who could be held accountable for significant failings was the Secretary of State, did not make for good policy, for good operational decision making, nor indeed for good politics.

A combination of all of the above led the then Secretary of State for Transport, Chris Grayling, to commission Keith Williams to be the independent chair of the review.

Keith was the former Chief Executive of British Airways as well as the deputy chairman of the John Lewis Partnership. Keith’s extensive private sector experience in complex customer facing businesses including in transportation, as well as dealing with industrial relations at BA and the partnership model at John Lewis, meant that he had much he could bring to the review. And the very fact that he has stuck with this journey throughout this time is remarkable in itself.

So tonight, I want to be clear on why I believe his findings and recommendations remain legitimate by:

- reminding us of the state of the industry before the Williams Review began;

- covering and analysing the six critical problems that the Williams rail review made – and the impact of the pandemic on the sector;

- showing how those problems are still relevant today, and why the reforms proposed are an important contribution to the future of Britain’s railway.

A reminder of the railways post privatisation

Franchising

The Railways Act of 1993 followed the election of the major government in 1992. It came at a time when the use of the rail network had been more or less in continuous decline since WW2. Its' overwhelming focus was to reduce the burden of the railways to the taxpayer.

British Rail was broken up into over 100 different businesses in the private sector. Most of those companies were designed to be profitable from rolling stock leasing companies, infrastructure maintenance businesses, technical and back office service providers. And the largest of them all – Railtrack – the monopoly owner and operators of the core infrastructure which would be subject to economic regulation, not dissimilar in many respects to that which had developed in the previous decade in other utilities.

None of these entities required subsidy because all subsidy was to be paid to the operators of the train services which would then be procured via a competition.

Principally, competition would take place for the market rather than within the market, recognising the network characteristics of fixed infrastructure which meant that on track competition had natural limitations. That is not to say that no competition on the railway was envisaged. But it was, I believe, never a key part of the political philosophy, though it was certainly a concept that some commentators found attractive.

The government invited private companies to bid to run services on the rail infrastructure using rolling stock leased from leasing companies. These franchises were awarded through a process of competitive tendering, with franchises intended to last for a minimum of seven years and cover a defined geographic area or service type. Minimum service levels were set out in their Passenger Service Requirements which utilised the British Rail timetable of 1993.

Winning bidders were essentially decided on the basis of lowest net cost to the taxpayer. Bidders quickly realised that, whilst cost control was a key component, the single biggest determining factor of your success in the competition was likely to be the level of revenue growth that you were prepared to assume.

Sadly, the system was never especially stable. The first large fissure came with Railtrack being placed into administration in October 2001.

The causes of the collapse of Railtrack are well documented and I won’t go into too much detail.

Railtrack’s record had seen a number of serious and tragic safety incidents, such as the Ladbroke Grove rail crash of 1999 where 31 died. And just over a year later the Hatfield rail crash happened, killing four people, which effectively brought Railtrack to an end.

The crash led to speed restrictions and track replacement works across the majority of the national network, leading to unprecedented levels of disruption for more than a year.

It was estimated to have cost the taxpayer £580 million and exposed both the inadequacies of the funding settlement with Railtrack and the very material gaps in its contracting strategies with its infrastructure maintainers.

By this point the Blair government was into its second term and at the end of 2001, Railtrack ceased to exist and was replaced by Network Rail. Still notionally a private company but one with no shareholders other than the UK government.

At more or less the same time as Railtrack collapsed, the Labour government set up the short-lived Strategic Rail Authority. The SRA was perhaps the first recognition that the original privatisation architecture had a fundamental flaw in not creating space or accountability for a guiding mind. That role for a guiding mind had begun to emerge where it became clear that, after two generations of decline in use, the nature of the economy in Britain was shifting in a way that meant rail travel, and especially commuting by rail into city centres, was an increasingly significant driver of economic activity.

Whilst the SRA had the network level oversight to better manage franchising, its formulation missed the opportunity to provide the industry with a guiding mind that can balance the needs of the industry, chiefly because it was decided not to include Network Rail as part of the SRA. This was a decision mainly taken because there was strong ambition from within government to keep Network Rail’s assets (and debts) off the government balance sheet.

But in doing so, it failed to tackle two fundamental issues. Firstly, no-one led timetable development and the efficient allocation of scarce capacity. Secondly, the P&L remained fractured and at best opaque. Operators were incentivised to perform in a way that was essentially indifferent to the network implications – a classic case study in the tragedy of the commons. Meanwhile, Network Rail was essentially indifferent to the revenues the system was generating and protected from the downside risk and prevented from sharing in the upside. Monopoly with essentially no whole system incentive.

In practice, the SRA turned out to be a short-lived experiment and in 2005, a new railways Act took decisions around financings back to Whitehall under the responsibility for the SoS for Transport and her or his officials.

Setting aside the collapse of the second franchise on the East Coast Mainline, the first decade of this century was a relatively stable time with strong growth in passenger numbers and a strong market for franchises with a sustained improvement in subsidy line for HMT and the taxpayer.

That is until the collapse of the West Coast franchise competition in 2012. The subsequent Brown Review set out a number of issues, but there are two that are particularly relevant for us:

Firstly, the franchising system was generating undesirable behaviour from bidders during the competition stage – bidders were being overly optimistic in their revenue forecasts because they knew that government support for revenue would support them after the first couple of years. In addition, as franchising trended towards fewer and larger franchises, each competition became more ‘make or break’ for bidders. This, combined with the revenue support, encouraged excessively aggressive (and unrealistic) bidding.

Secondly, the government were being too prescriptive in their franchising specifications – in the original 25 franchises there was relatively little prescription. Subsequent rounds however saw both the SRA and the DfT become increasingly prescriptive, not just about the outputs they wanted to contract for, but the manner in which they should be delivered.

The system architecture of the railways

In the days following the creation of a privatised rail network, the split between private and public ownership was clear.

Railtrack was privately owned whilst private sector train operators ran trains leased from privately owned organisations.

The state’s role was also clear – namely to award franchises and provide regulation.

The beginning of the blur towards public and private responsibility and ownership started when Railtrack plc was reconstituted under Network Rail Infrastructure Limited, albeit nominally in the private sector. The fragility of this artifice was ultimately exposed by the ONS in 2014 when Network Rail was reclassified as a public body and it’s by now £34bn of debt was brought onto the government’s balance sheet. This change naturally led to a heightened increase in oversight from government.

So, from a system in 1993 which envisaged full private sector participation and a light touch government role in a sector which was probably expected to contract rather than expand… some 20 years later, we find ourselves with the single largest player, Network Rail, being a public body, with Whitehall officials directly accountable for the procurement and management of private sector operators.

And the challenges of growing capacity on a network which was struggling to cope with the needs of the decade, never mind of the next generation. At the same time as parliament was overwhelmingly supporting legislation to facilitate the next phase in the UK’s high speed network.

And yet the system architecture of contracts and incentives and industry processes had barely changed by one syllable.

The mechanism that had been designed to support the model of the 1990s were now fundamental to the problems that were emerging in the second decade of the 21st century.

Before we cover the findings of the Rail Review, I want to give you further context on how the railway has performed since privatisation – covering usage (and its causes), passenger satisfaction, performance, and how the industry’s finances have changed.

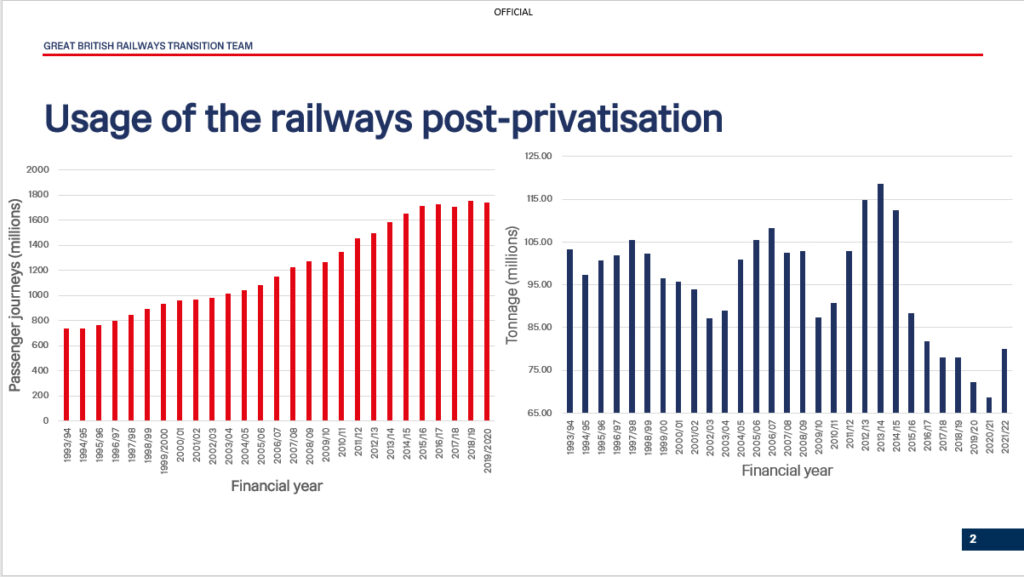

As I’ve already mentioned, since privatisation, the usage of the railways has significantly increased.

Between 1994 and 2019, passenger journeys increased by 128% from 735 million to 1.75billion – rail’s highest share of distance travelled by transport modes since 1965.

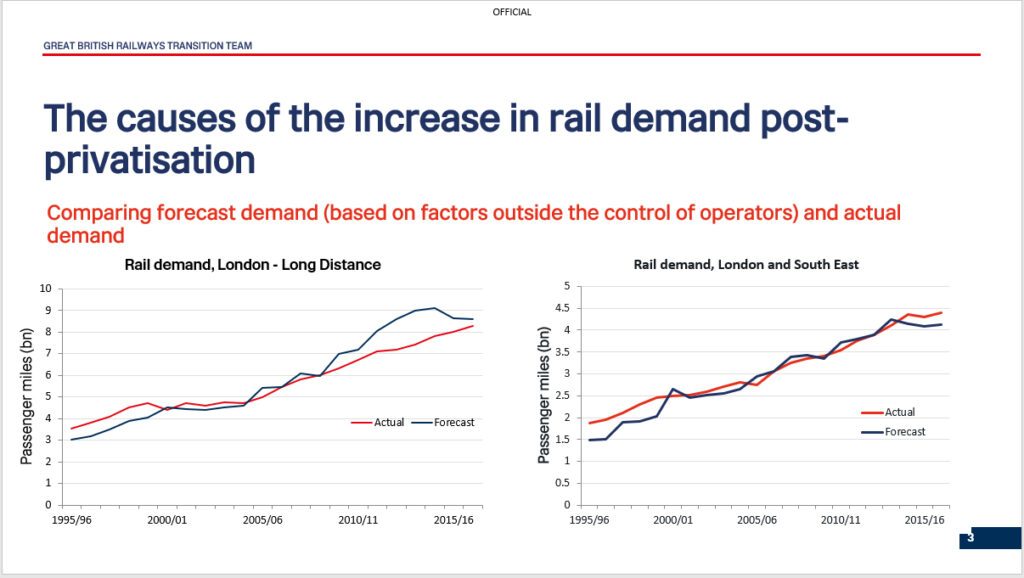

Some might say this growth was largely down to their brilliant commercial acumen. But the truth is rather more complex.

It is true that privatisation and the introduction of franchising brought about benefits that enabled passenger growth, there are several other causes which look to be more influential in driving growth:

GDP growth – since 1993 we’ve seen an average of 1.97% of growth in GDP. An increase in GDP has led to a greater number of jobs on offer combined with sustained wage growth – with an average annual wage growth of 4.16% per year.

An increased level of jobs on offer naturally impacts the level of business travellers and commuters Britain’s railways see. Whilst an increase in disposable income again impacts the number of leisure travellers the railways see.

Population growth – the growing population has naturally had a large impact on the number of passengers on Britain’s railway – especially those of working age. The UK’s population grew by 9 million between 1993 and 2019.

Low unemployment – In 1993, unemployment was 10.4%, but between 1994 to 2019, the average unemployment rate was 6.15%. These statistics when seen in combination, show that the socio-economic conditions of the UK as a whole were prime to support a growth in those using Britain’s railways.

Fuel prices and road congestion – the cost of travelling by rail has gone up by over double the rate of inflation. However, the costs of travelling by road have outpaced rail. Comparing to the base from £1 in 1997, inflation moves that to £1.55, rail costs are £2.32, whilst road costs are £2.50.

Whilst these macro-socio-economic points have driven passenger growth, it would be churlish not to recognise the impact that franchising and privatisation had on the increase of passenger levels.

There are some clear areas where privatisation made rail a more attractive proposition. The investment in customer service that train operators gave and the improvement in rolling stock under train operators supports a better passenger experience, whilst train operators with a revenue risk were more commercially aggressive to fill empty seats through their advanced fares.

Remember, these increases in passenger numbers were not a stated aim of privatisation, and it was not the intention of privatisation to make sure that train operators considered the capacity for this growth and encourage the capital investment required to manage it.

As passenger volumes and train miles grew, congestion on the rail network exposed the necessary trade-offs between track and train that were required to manage it. Ultimately, there was no system level oversight that ensured the network was being used efficiently.

The government found itself buying infrastructure interventions via a typical five year periodic review process, and rolling stock and train service improvements via franchising contracts, which might have entirely different timescales and assumptions. And in some cases, would be prescribing outputs 5-7 years before they were planned to be delivered.

This was a key element of what was at the heart of the May 2018 timetable fiasco.

Without that oversight and through the negative behaviours driven by the contractual arrangements mentioned earlier, individual actors were able to, intentionally or unintentionally, gain for themselves at the expense of passengers and government.

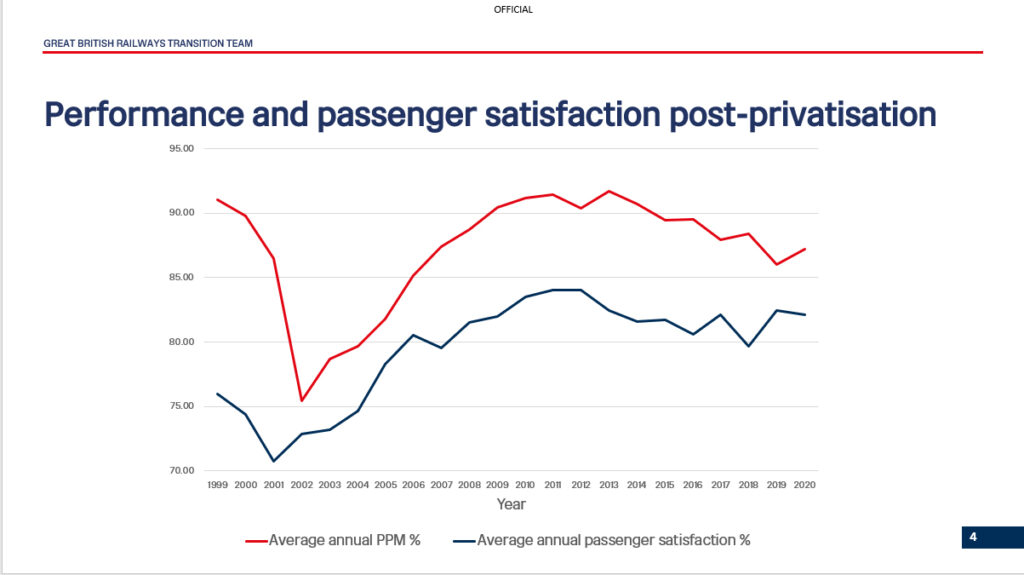

Whilst usage has continuously improved since privatisation before the pandemic, passenger satisfaction and performance reliability has not precisely mirrored that.

Passenger satisfaction has increased since privatisation, however it is closely related to performance and reliability. Consequently, we know that pre-pandemic, passenger satisfaction was at its lowest in a decade, with more than one in five passengers not satisfied.

The industry metric for performance and reliability, Public Performance Measure (PPM), measures the percentage of trains that arrive less than five minutes late at their final destination, stretching to 10 minutes for long-distance trains. The last time PPM was above 90% was in 2014, we’ve seen that fall to a pre-pandemic low of 85.9% in 2019. And yet operator after operator had won their franchise contract on the back of improving not declining train service performance. But these contracts took insufficient account of the effect of congestion on the network’s output. And there was no practical means of the DfT enforcing non-compliance with a contractual obligation, especially when the cause turned out to be physics!

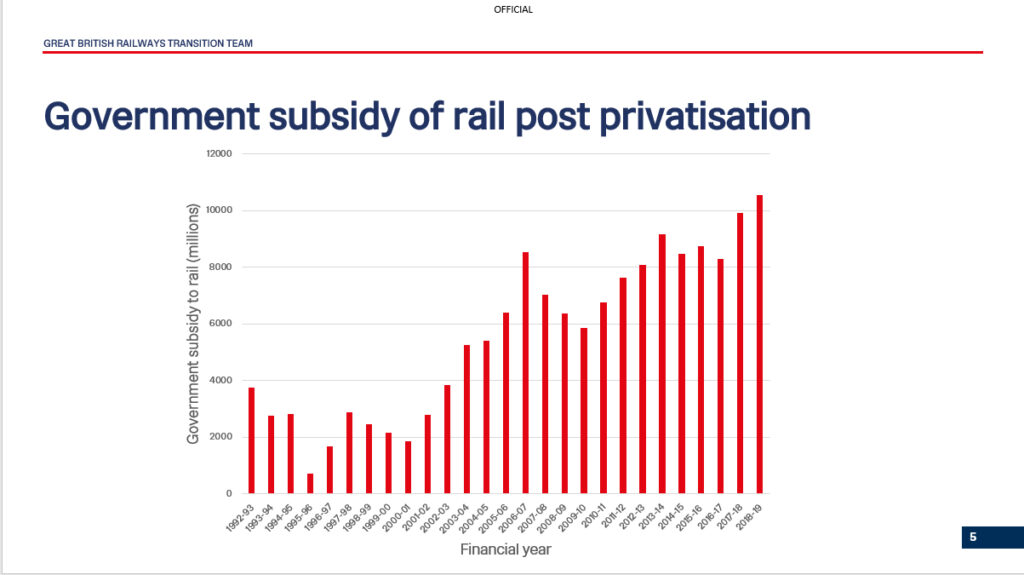

Sadly, from a taxpayers perspective, increasing passenger numbers were not sufficient to equate to a net cost reduction in the sector. The cost of providing the capacity, rising customer expectations on service quality and an aging asset base has meant a somewhat surprising profile.

For government, the level of subsidy they have had to provide has increased greatly. In the first ten years following privatisation, we saw total government support of on average £2.39 billion a year. By the end of 2018/19 it was £9.18 billion.

And the profile of operating subsidy to train operators flipped in the last decade from a net premium of circa £500m to a deficit of the same value by 2019.

As I say, contrary to popular belief in some circles, this increase in subsidy has not largely gone to shareholder dividends but to the replacement of ageing or life expired assets, and significant projects to improve the quality of service offered by the system.

The average real price of a ticket has grown by 10.3% since 2004. But even before the pandemic, this level of government support was proving difficult to sustain.

So in 2018, there were several immediate triggers for a substantial root-and-branch review into the railways.

In February 2018, the Virgin Trains East Coast franchise collapsed.

With revenue being lower than expected, the company registered a loss of around £200 million to date – highlighting how fragile the franchising system and its revenue forecasting was to exogenous economic factors.

As we’ve already discussed, this was highlighted as a problem in franchising in the Brown Review back in 2012, and the result of it was that once a business missed core objectives in the early years of the franchise, there was no real prospect of it recovering.

Immediately afterwards, the May 2018 timetabling crisis happened. A result of significant misalignment between operators, Network Rail and government resulting in thousands of cancelled services and prime time news headlines.

The then Secretary of State for Transport found himself as the only individual who appeared to have clear accountability for the functioning of the network.

This was the context and background that greeted the team behind the Williams rail review.

The Williams rail review identified six critical problems with Britain’s rail sector.

The first finding was that the rail sector often loses sight of its customers, both passengers and freight.

This meant that passengers and freight customers found that too often, the railways were not getting the basics right; trains were not running on time, it was hard to buy a ticket, and the system was not easily accessible to all who wanted to use it. And there’s a lot of evidence to support this conclusion.

On punctuality – we touched on this before – in the last ten years we saw a steady decline in train performance. Driving performance improvements is difficult when Network Rail and operators aren’t working towards the same set of incentives, and when the infrastructure provider doesn’t have the ability to be able to manage the timetable appropriately to meet their needs.

On the difficulty in buying tickets, recent analysis from the Rail Delivery Group, discovered that there were nearly 55 million different fares on offer. Passengers have told us that fares are too complicated, and we know, unsurprisingly, that value for money is a core component in passenger satisfaction. If fares are too complicated for passengers to trust they have bought the most cost-effective ticket through technologies that they would regards as ubiquitous in other parts of the economy, then we are unlikely to maximise our market share.

On accessibility, research shows us that, despite the desire to travel more frequently, more than two thirds of people with a disability anticipate problems with their ability to travel in the future and as a result, lack the confidence to do so. This is a challenge that will only increase. Future population trends indicate up to five living generations, and the railway is not prepared for that.

The industry often lost sight of its customers, frequently because of drivers of the current system such as misaligned incentives and a lack of clear industry impetus to drive forward complex change.

The second, and related finding from the review, was that the industry is missing opportunities to meet the needs of the communities it serves – the rail sector was seen as unresponsive to the needs of local and regional partners, with decision-making too far removed from the people and places that the railways serve.

I’ll take you through two examples:

Firstly, on being unresponsive to the needs of local and regional partners – it took the rail sector two years to approve a half-hourly Harrogate to York service, despite the fact that North Yorkshire County Council were willing to fund the £12 million scheme.

Secondly, a lack of flexibility is resulting in being unable to take advantage of opportunities in the local community – subnational-transport bodies like Transport for Greater Manchester are introducing regional tickets through their ‘Bee Network’. These are multi-modal transport tickets but are unable to include rail because of the industry’s inability to integrate with their ticketing offer.

Thirdly, the review found that the industry is fragmented and that accountabilities are not always clear – the industry structure is complex and fragmented, being unclear who is in overall charge across track and train. On a complex, interdependent network, this was seen to be holding the sector back.

A clear example of this is the May 2018 timetable problems. The inquiry that followed showed that Network Rail failed to take sufficient action on the risks that it was best positioned to understand and manage, the relevant operators had planned their service on a different set of assumptions, were not informed of that risk, but also failed to communicate adequately with passengers once the disruption occurred, whilst neither the DfT nor the ORR, despite the information and power to do so, actually sufficiently tested the assurances they received from the industry.

However, whilst each of the key factors in the industry did not perform to expectations, the underlying failure was the disconnect between the franchising process and the infrastructure delivery plan, which became visible and impactful through the timetable being unable to reconcile these differences.

When it became clear that the infrastructure was unable to deliver the timetable, there were no changes made because of the contractual arrangements in the franchise agreement.

The first three points from the Williams Review, and those that will follow, I think are prime proof points of the next critical problem that the Review identifies – the sector lacks clear strategic direction.

The rail sector lacks a single guiding mind to define its priorities and develop long term approaches to critical challenges such as modernising fares and ticketing and improving sustainability.

I’m going to take you through a couple examples which shows that, if the industry was strategically aligned, it wouldn’t have made these decisions:

Firstly, competing priorities which resulted in a loss of focus on overarching goals. An alliance between Abellio ScotRail and Network Rail was agreed at the start of their franchise in 2015, to further integration and deliver efficiencies. Abellio’s primary motivation, understandably, was to drive value for their shareholders whilst fulfilling their contractual obligations. Whilst Network Rail’s primary focus remained on long-term agreed regulatory outputs with no remit to contribute to maximising industry passenger revenue.

Ultimately there was little alignment of overarching goals and, far from driving collaboration, there are still disputes between Abellio and Network Rail on who’s financially responsible for losses that occurred following planned disruption in March 2016.

The lack of strategic direction has also resulted in short-term revenue-based decision-making causing capacity reductions – many operators choose to serve York to Newcastle to access this revenue stream. This has meant that revenue mechanisms encourage trains to closely track each other, meaning the route is congested, causing problems when there are delays. And restricting the ability to introduce non-stop services which drive the very revenue line which has underpinned the significant investment in the route.

A more balanced approach to pathing the trains could actually lead to better commuter choice, ultimately benefiting the customer and taxpayer.

However, the lack of strategic direction has prevented that – as the franchise decisions are made separately from Network Rail whilst the ORR awarded additional access rights based on incremental choices.

The penultimate finding of the review, was that the industry needs to become more productive and tackle long-term costs – the industry was not widely trusted to make cost effective decisions.

Rather than adopting smarter approaches that make best use of all available levers to address problems (fares, timetable, rolling stock and infrastructure), the industry was perceived to default to expensive, capital-intensive solutions. Workforce reform was not being delivered.

There are plenty of examples for this, let me take you through just two:

The first is on non-cost-effective decisions – across the network, there are countless examples of the duplication of operational staff. Kings Cross is but one example. Each operator will have their own station manager, on top of the Network Rail station managers. Not only does this unnecessarily increase costs the industry faces but it’s also confusing for passengers, reduces accountability and requires significant effort and focus that could be spent elsewhere in aligning communications.

And we also have examples of non-effective workforce reform – the current commercial and fragmented system are notorious for having no coherent approach to workforce pay and conditions.

This means that train drivers in particular have been able to ‘bid up’ their pay and T&Cs through competition between operators, whilst it makes complete sense for operator X to hire drivers from Operator Y and save the training costs. The short-term nature of franchises means it’s very often entirely rational to pay more in the short term for peace and not consider the long-term cost implications for the sector. Whilst the punitive penalties on Network Rail for service disruption mean it is subject to similar perverse incentives to play the short and not the long game.

And lastly, the review found that the rail industry struggles to innovate and adapt – there was a common view that the rail sector struggled to innovate and embrace new technology, lacking incentives to empower its people to modernise and adapt.

We see this clearly in the persistence of paper tickets across the National Rail network, and a failure to properly introduce either London style pay-as-you-go ticketing or smart tickets.

The fractured nature of the industry doesn’t encourage it – there was a standoff for multiple years that had to be resolved by the DfT, as GTR customers getting off at Cambridge station couldn’t use their GTR smart-cards because the station is managed by Greater Anglia.

This is especially poor when you consider that smart card technology was developed at the same time as the Oyster card, and only 20% of available fares are on offer for smart cards.

Whilst in that time, 90 million Oyster cards have been issued. And TfL haven’t stopped, moving on from Oyster and pushing customers to use contactless bank cards.

There are several reasons why the industry has struggled to innovate and adapt like other similar organisations have:

- The split of accountabilities across the sector has confused the direction it should take and made it unclear who should lead. For example, in driving a better Fares, Ticketing and Retail offering – should it have been the government, or should it have been the train operators?

- The relatively short-term nature of franchising also hasn’t helped – a business concerned that they may only have 2-4 years to operate their services will have very short pay back thresholds.

We should also remember the politicisation of even minor decisions that has acted as a drag on change. Any innovation that might be politically contentious can be subject to a level of risk adjustment, scrutiny and caution that is simply uncharacteristic of a dynamic or innovative sector of the economy.

The Williams Review highlighted these issues and made it clear that the current structure today, with its lack of incentives and level of government intervention, mean that, without change, the railways’ ability to innovate and adapt are impeded.

COVID

Before we move into the proposed solutions, I want to cover the impact that the pandemic had, and is very much still having, on the industry.

The Williams Review was started in 2018 but not published until May 2021, so that it could reflect the initial impact of the pandemic. Now that we are 18 months further down the line, has the pandemic made Williams’ more relevant, or less?

On industry finances

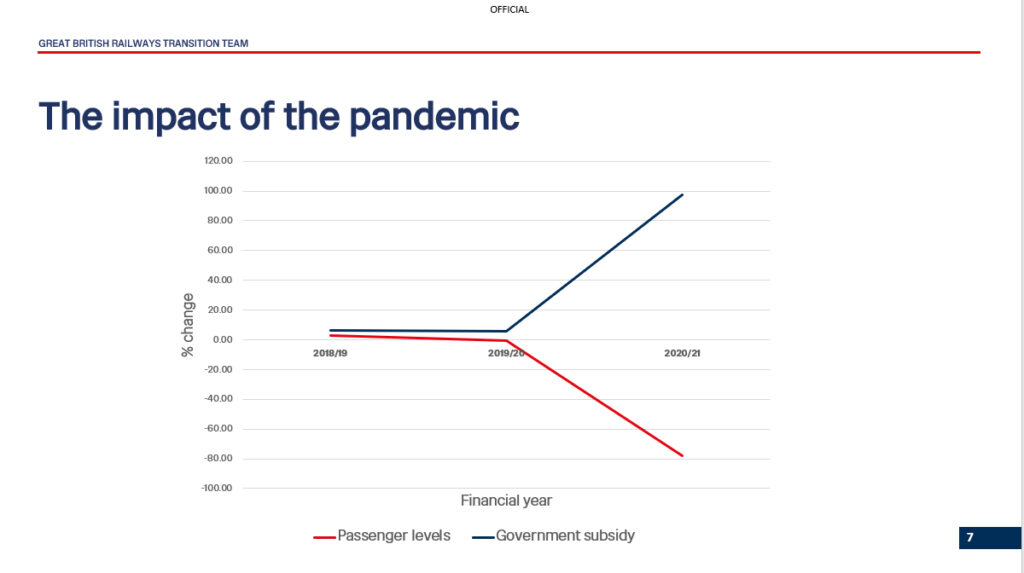

In April 2020, passenger numbers fell to levels that were last seen in the 1850s. By the end the year, there was a 77.7% reduction. Fare revenue dropped by £8.6 billion, to just £1.6 billion – putting the industry in a financially unsustainable position – total government funding to support the day to day running of the railway jumped from £4.4bn in 2018/19 to £17bn in 2020/21.

These impacts are not entirely temporary. Whilst we have recently seen revenue recover to between 80-85%, rail has and will struggle to breach that as a result of long-lasting changes in passenger behaviour. 97% of those who travelled on the railways before the pandemic have returned, but their behaviour has changed. Commuters have only recovered to 57%, business travellers to 37%, whilst leisure is at 118% of pre-pandemic levels. Whilst we take the positives in leisure recovery, the extra revenue received from that does not plug the revenue gap from the drop in commuters and business travellers – currently at £2 billion a year.

And these changes may well be here to stay. We know that 84% of workers required to work from home because of the pandemic say they plan on continuing to do a mix of this. The Williams rail review highlighted that the industry often lost sight of its passengers and customers, as well as missing the needs of the communities it serves.

The lasting impacts of the pandemic have only made Keith’s findings more relevant – to support rail’s recovery it will need to adapt to our passengers’ changing needs and behaviours.

On the public/private divide

As well as the lasting changes on passenger and financial levels, the pandemic also had a lasting impact on the architecture of the rail system. The pandemic exacerbated greater and greater public control over the operators.

Whilst it’s true that more contracts than ever are now directly in public hands through what is known as the Operator of Last Resort, of more significance is the fact that all other operators, as a condition of the support which the government provided them with, have been moved from franchises to National Rail Contracts. These arrangements mean that the Government bears all cost and revenue risk, and operators are paid a small fee to run the service based on a business plan that is submitted annually.

At present all revenue risk sits with HMT and all cost risk sits with the DfT though there are mechanisms in the contracts to include some degree of cost incentivisation in due course.

This situation then is in stark contrast with the model that was set out in the 1990s and is a clear indication of just how far the rail system in Britain has moved, sometimes slowly, sometimes more dramatically, from the clarity of that original logic.

So today we have a public sector infrastructure body, private sector train operators with little or no incentives on cost or revenue, very detailed decision making in the hands of government, and yet with the same architecture of contracting and incentives that were designed some 30 years ago for a very different era and model.

Furthermore, we have an ambitious set of investment interventions, committed to by both major political parties, to develop high speed services and improvements in the Midlands and the north to drive economic growth….

…And yet no entity to ensure that the passenger outcomes of these huge infrastructure interventions at eye watering cost can be confidently realised in a sector where one of many individual factors can wilfully, or unintentionally, sabotage these strategic interventions.

I hope that from what has gone thus far you have some sense of the challenge or challenges. These challenges existed before the pandemic and have only been made more existential by it.

Since privatisation, there have been more than 30 reviews – and yet the industry still faces systemic problems. Most of these reviews made similar conclusion – that rail is profoundly and unnecessarily complex.

But what these reviews failed to group the rail network is a system.

And for the fundamental changes needed to reflect the profound shifts in usage, funding and passenger behaviour, a whole system response is needed.

At the heart of the Rail review are three fundamental characteristics:

- a degree of separation from political control that will allow an intense focus on the needs of the users of the rail network as the best means of ensuring its delivers for the economy

- the establishment of a guiding mind to ensure that, where necessary, strategic interventions can deliver the outcomes they are intended to secure

- a strong role for private sector participation and innovation governed not by outdated, over prescriptive contract mechanisms or dogma on incentives, but by the characteristics of the markets which they are operating in.

The Williams Review recommends a guiding mind that sits separately from government, manages the rail infrastructure, the timetable, awards Passenger Service Contracts (to replace franchising), whilst creating and implementing policies for those who access the railway.

The Review recommends a strongly regionalised organisation, where decisions are made closer to, and in collaboration with, the communities they serve. An organisation that can remove the excessive and unnecessary duplication that exists across the industry and offer a better financial deal for the government and taxpayers.

This doesn’t mean creating more complexity – in fact it’s the reverse.

Rail reform as proposed by the Williams Review encourages simplicity and I want to take you through what rail reform must do to achieve that, to deliver the systemic reform needed.

Firstly, rail reform must create a simpler, better railway at arms’ length from government, accountable for co-ordinating the network nationally with strong regional businesses focused on local delivery.

This is essential because, by removing itself from government micro-management whilst being more strongly connected to the communities it serves, rail can understand better how it needs to adapt and then have the freedom to do so. The freedom to do so has been a core recommendation of the Williams Review – highlighting the problems that arise for the industry with too much government centralisation.

With the current industry ways of working, this is not possible.

Most decisions are entirely centralised, made far from the communities they impact. The pandemic only exacerbated this level of highly detailed specification and oversight, through the move to National Rail Contracts.

In addition, the current architecture of the rail system makes simplification and improvements difficult. With the government and operators negotiating on service levels, Network Rail are left to collate the timetable based on the contractual arrangements – not fully balancing the infrastructure needs and the desires for service levels.

The ORR finds itself sustaining incentives regimes which make little or no sense in today’s system but which it is required by law to impose. If revenue risk ever returns again, the innovation and customer-focused improvements delivered by Open-Access operators, are seriously constrained.

Franchised operators are rationally incentivised to minimise the amount of spare access on their route to avoid abstraction from a new entrant, and there’s no strategic oversight of this to ensure that capacity on the rail network is fully utilised.

The combination of these issues means a complicated system with few incentives to deliver upgrades for our customers.

To manage these tensions, Keith Williams recommended a guiding mind to balance the need for the effective management of trade-offs across operators, the infrastructure provider, and government.

His view, strongly and publicly supported by the permanent secretary, was that it needed to be independent from Ministers – for the benefit of the industry as well as Ministers.

Earlier I touched on how, during the May 2018 timetabling crisis, the only person left accountable was the Secretary of State. By enabling an independent guiding mind (via being an arms-length body) there can be clearer accountability – benefiting Ministers.

The railways benefit greatly from this as well. Ministers can guide, instead of making operational decisions. The current ways of working has involved too much political intervention – with previous Rail Minister’s being asked to make decisions such as whether the 01:05 Waterloo to Southampton should have an amended service Sundays to Wednesdays.

This is not about a denial of the reality of political accountability or unfettered independence; it’s about appropriate separation – something that I hope will resonate with regulators in the room.

Secondly, rail reform must fix Britain’s rail system by unleashing the potential of the private sector through a simpler structure, with good and credible competition in order to rebuild the network and improve services for passengers.

80% of spend in the rail sector is with the private sector.

They have been a critical component in the delivery of effective services for rail’s customers for nearly 30 years now and will be continuing to do so going forward. For the sake of the government and taxpayers, the railway must drive excellent value for money from the private sector, whilst the private sector needs assurances that they are operating in a system that will meet their needs as well.

The private sector delivers several benefits to the railway:

- An intense, commercially led customer focus – the competition to run these services can be a powerful driver of growth and efficiency providing the right incentives are in play.

The private sector are often those closest to the customer and able to adapt to their needs better because of the expertise they bring, the agility of their movement and the risk they bear. The Virgin franchises on the East and West coast pioneered this – improving customer service, offering new benefits such as BEAM (equivalent to in-flight entertainment) and instant delay-repay for those travelling on advanced tickets. As the railway looks to drive revenue recovery as well as to improve passenger satisfaction, the private sector’s ability to innovate and find new ways to attract and retain passengers is critical. - In general, the private sector better fosters a culture of innovation and adaption – through consistently embracing new technology, the private sector is better able to drive efficiencies and give a better passenger experience – we see that in the improvements to rolling stock over the recent years.

- A relentless focus on cost control – having to focus on revenue and costs simultaneously can help create a better balance towards long-term financial sustainability. The guiding mind brings the opportunity of a whole P&L perspective, something that has been absent for some 30 years. It can serve to unlock true private sector innovation and avoid the pitfalls that come with the artificial segregation of costs and revenues. We know that the industry right now is too fragmented – all too often operators have little motivation to care about capital investment costs, whilst Network Rail has little incentive to care about revenue. It doesn’t drive the best outcomes.

- Reduce the time it takes to bring in innovation – through creating a simpler, better sector, a guiding mind can reduce the bureaucracy that gets in the way of innovation. It might seem incongruous but one of the single biggest obstacles to strategic change has been the revenue incentive mechanism which acts as an obstacle to contract adjustment and encourages individual parties to defend their territory and not support the best outcomes for the system as a whole.

Thirdly, rail reform must demonstrate to current and potential users that it is simpler to use than they think, and that they can trust the product they have been sold is the best product for them. Essentially, they need to know that rail system is on their side.

The Williams Review highlighted clearly that passengers felt the fares offering are unnecessarily complex and are concerned about the value for money they receive on their ticket.

Less than 50% of passengers currently feel that they receive value for money. If passengers don’t believe that rail is trying to enable them to get the best deal possible, that has a substantial impact on passenger trust. As rail struggles to breach the 85% revenue recovery level, the industry cannot afford to be seen as untrustworthy.

The current way of working makes updating areas such as Fares, Ticketing and Retail difficult and inconsistent. Train operators concerned about their geographical patch have little incentive to change or make compromise for the benefit of train operators they may never interact with.

The example I used earlier of GTR customers at Cambridge Station unable to use their smartcards because it was run by Greater Anglia shows that, even when operators do overlap, they often fail to meet the needs of customers.

Improvements such as better utilising smart card technology are critical to being simpler and more trustworthy. Transport for London have a similar complex system of fares and yet, through the better utilisation of technology, very rarely do TfL fares get criticised for being too complicated to understand.

Fundamentally, rail reform must also cut the time and cost of delivering infrastructure projects by using simpler interfaces, reducing unnecessary red tape, encouraging innovation and essentially delivering the benefits that it promises to the users of the railway.

Complexity, competing priorities and bureaucracy have long delayed the delivery of infrastructure projects.

The current system of contracting disconnects the needs of Network Rail with the objectives of the train operators, whilst government policy is sometimes inconsistent in its implementation – leading to changes in scope. This ultimately costs the taxpayer more and delivers inconsistent results for our customers.

We saw this in the issues that plagued the Great Western Mainline Electrification project. Initially scoped in 2009 to electrify London to Swansea (as well as Bristol Temple Meads), what eventually transpired was the original cost of £874 million increasing to £2.8 billion despite a 20% reduction in scope.

There were many issues with the project – but what is important to note is the finding of the Public Accounts Committee that urged ‘track and train’ to better come together going forward so that delivery could be made more reliable and cost effective.

It is a shocking factor that almost none of the major infrastructure interventions that the government has invested in the railway in the last 20 years have fully delivered on the promise to passenger and freight users. Not because of lack of money or of professional competence, but because the misalignment of incentives in the architecture and the absence of any strategic control has made it all too easy for events and factors to disrupt.

We do not know what the future holds in terms of passenger and freight demand.

But we do know that the current system has demonstrated it is structurally incapable of efficiently delivering an agile response to shifting patterns of usage and demand that is anything other than incremental.

The penultimate need for rail reform is to ensure that the path to a fully decarbonised railway is an affordable one that unlocks the latent advantages of rail freight.

I hope I can take it as read that the climate crisis is not a threat but a reality. The railways have a core role to play in supporting the government’s net-zero ambitions.

The Williams Review was clear on this – rail has exceptional green credentials and needs improved direction across the industry to deliver the benefits it has the potential for.

Rail has consistently been the least environmentally impactful form of large-scale travel. Cars and taxis produce 51.8 million tonnes of carbon dioxide a year, aviation 15.1 million tonnes, HGVs 18.6 million tonnes, whilst rail produces just 1.4 million tonnes a year. Each freight train takes 76 HGVs off our roads, translating to 1.66 billion fewer HGV kilometres a year.

The rail industry must drive this growth further. We know as individuals and businesses across the country look to reduce their environmental impact, that they’re turning to rail as the solution – we see this in how leisure travel is often at levels higher than before the pandemic.

And companies are turning to rail freight. Just a few weeks ago Coca-Cola Europacific Partners announced the switch from road to rail to distribute its soft drinks between London and Yorkshire – meaning that some 2.5 million cans and bottles will be delivered by rail per day, helping to reduce carbon emissions by nearly 50%. The rail industry needs to take the initiative on opportunities like these and drive them forward.

The fractured nature of the current system can make delivering this growth difficult.

An inability to allocate capacity according to environmental benefit rather than conventional need for instance; a lack of flexibility which can mean that the time taken to serve potential new entrants can be off putting.

Equally there are long term freight customers who want confidence in long term deliver ability. Earlier this year I visited a quarry where they took pleasure in reminding me that stone had been quarried there since Roman times and that it was the railway who were the new kids on the block. These customers want long term investment partners.

And lastly, rail reform must enable a fundamental shift in the employment model.

We are living through one of the most awful manifestations of the shortcomings of the current model.

A failure of long-term workforce planning, an imbalance of relationships between employer and trades unions; the consequence of incentives that reward the short-term win and not the long-term productivity and a failure to reflect the communities we serve.

We are currently experiencing damaging strikes over job losses when there is a serious shortage of skills in the sector as a whole; trades unions who have been able to resist the sort of elementary working practices that would keep their members safer and that are utterly ubiquitous in other sectors; a generation of above RPI wage inflation setting expectations at a time when inflation means that’s simply not fundable and a workforce that is to full of people that look like me.

These are no accident or a function of negligence – they are by-products of the incentives in the current system. But they are not inevitable. A guiding mind could have a much more progressive approach to tackling these issues over a sustained period of time. It could facilitate grooming long-term skills development and deployment, in a sector where digital capability is going to be in high demand; it could reward genuine productivity not incentivise over reliance on excess hours; it could ensure effective co-ordination without either the politicisation of industrial action or the return of collective bargaining; it would champion a truly inclusive employment approach.

All of this and more will be essential if we are to deliver essential savings of at least £1.5 billion a year against efficiency and productivity and we are now paying the price for that.

Conclusion

The lesson of privatisation of the railways in the 1990s is fundamentally that the system has to be able to adapt or it has to be changed. A model designed, above all else, to reduce the burden on the taxpayer of a static or declining market, was able to cope with more than a doubling of passenger volumes, all the time there was spare capacity in the system and the private sector was ready to take risks on essentially exogenous revenue growth. That’s no mean feat, and at times, I may have been guilty of understating the achievement that this represents. That is not my intention.

When the network capacity was, in effect exhausted, the system lacked the ability to allocate existing capacity more efficiently – no actor could take a guiding mind role and the complex web of contracts and incentives served to embed vested interest, and not new entrants or innovation.

As a consequence, expensive infrastructure interventions became needlessly expensive; franchise operators failed to deliver on many of the promises they had committed to and the misalignment between the two meant service quality and reputation has been seriously jeopardised.

Oh, and the appetite to catch a nasty cold when the exogenous revenue factors turned against you understandably diminished significantly when it became clear that this was increasingly the norm and not the exception. All this before the devastating one off impact and systemic shift in usage that COVID has presented.

Thus, the rail industry finds itself in something of a no-man’s land. Its base model is manifestly no longer relevant given the shifts in purpose and responsibilities and expectations in the 30 years since it was designed; its current temporary arrangements are a necessary evil, but they really are evil – no long-term incentives; very, very high level of HMT and DfT control and detailed operational decisions being taken my Ministers and officials.

And yet there appears to be real cross-party commitment to huge investment in new lines and upgrades that will only be accessed if they are truly integrated into the existing network where they can benefit from the network economics that are fundamental to successful rail systems, wherever they are found.

And of course, the political situation at the moment is uncertain to say the least. Our third Secretary of State for Transport in under 2 months is facing a bulging in-tray. It was not surprising that the then Transport Secretary announced a couple of weeks ago, that the Transport Bill needed to create Great British Railways would be pushed back into the next Parliamentary session.

This caused some over-excitable journalist to proclaim that the Plan for Rail was dead. I believe they are mistaken because reform is overdue.

The diagnosis offered by Keith Williams is forensic and robust; the post covid environment has added fuel to the burning platform and the fundamentals of his remedy are compelling – a simpler, better railway for everyone in Britain.